For the first time in the festival’s history, it didn’t rain at all. The atmosphere was amazing, and Meltingpot was packed to the brim.

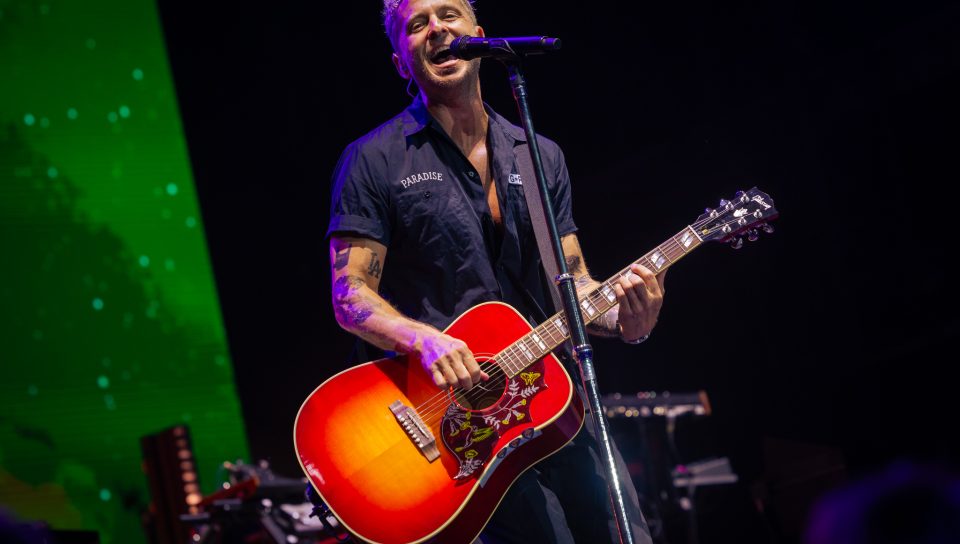

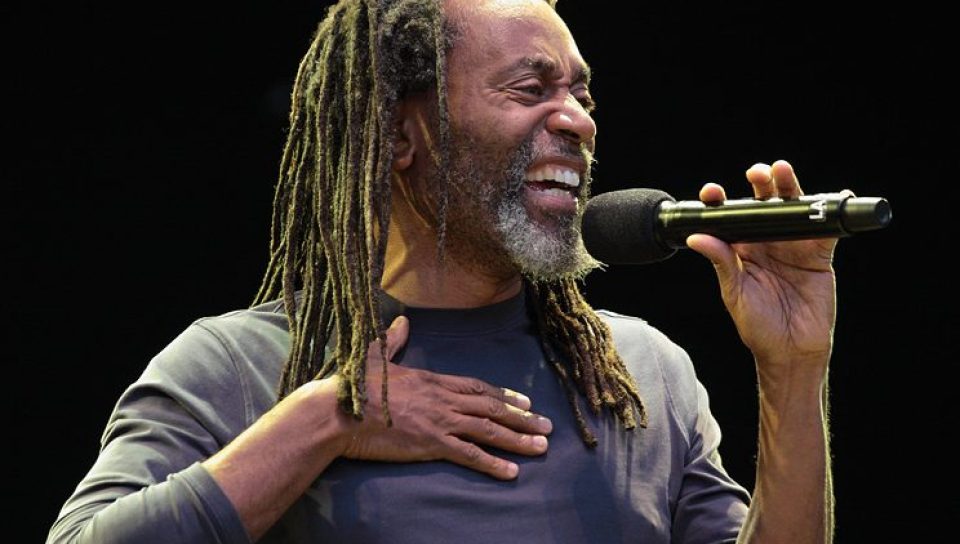

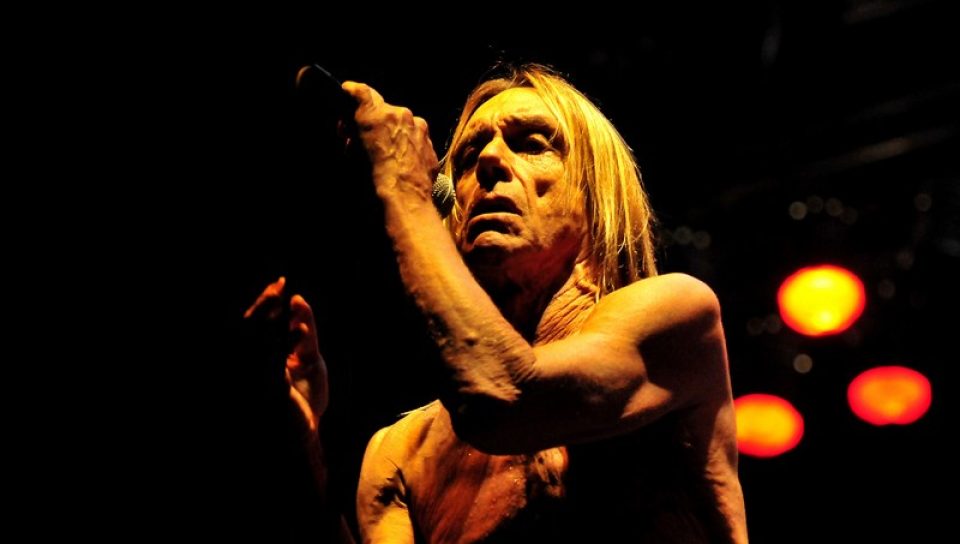

Lenny Kravitz, Sam Smith, Sean Paul, Zara Larsson, Tom Morello, freekind., James Blake, Sam Garrett, Miss Monique, ANYMA, Tangerine Dream, Genesis Owusu, D.Y.K., Lake Malawi, Lenny, NobodyListen, Mig 21 and others…